A biased view of the development of engineering geology in New Zealand

Background

Engineering geology is the application of geology to engineering for the purpose of ensuring that the geological factors, including hazards, affecting a site or scheme are recognized and taken into consideration during the design, construction, and maintenance of the engineering works.

Unfortunately, in the past misunderstandings frequently created friction between the engineers and geologists. The problem was that all too often the geologists did not have any real understanding of engineering principles and were prone to a lofty, scientific style of report or oral presentation that was foreign (and therefore nearly useless) to the engineer.

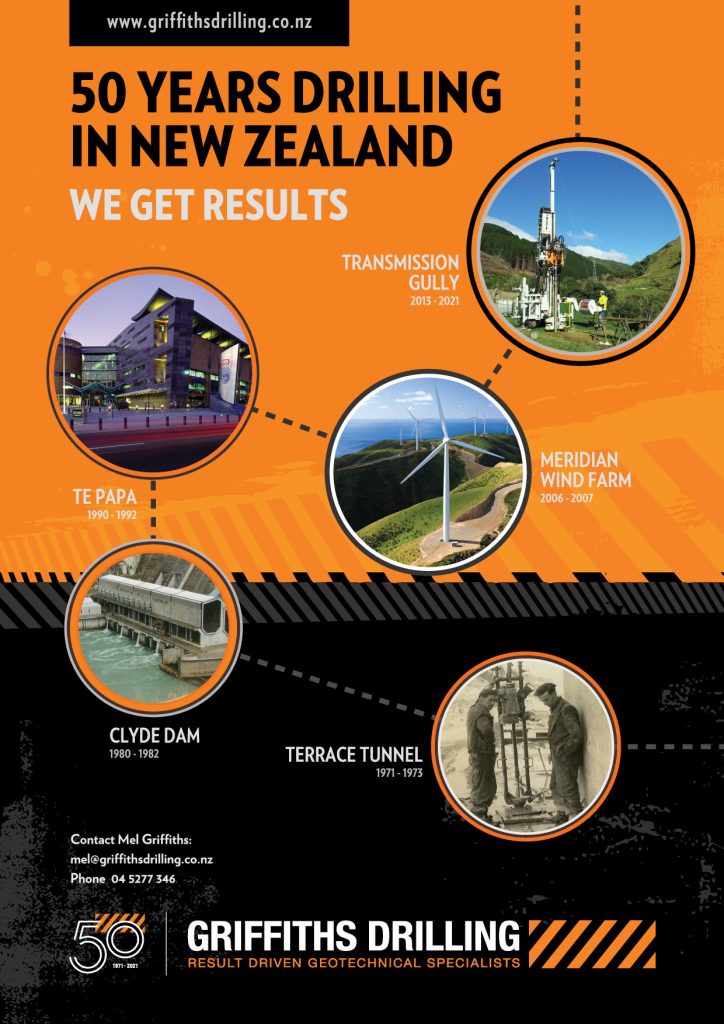

In extreme instances, some project engineers minimized the importance of adequate geological investigations or scorned the data and recommendations of geologists as of little practical value. In my own experience, this was exemplified by a quote pinned to an (un-named) engineers office door during the construction of Clyde dam which advised us that the only information required from the geologists was the answer to the question “is it rock of ages, or is it shit?”

Sadly, some of the resulting engineering works ultimately experienced difficulties and/or failure due to not understanding the geological conditions. Well known examples include the St Francis Dam (1928), Baldwin Hills reservoir (1963), the Vaiont landslide (1963), along with the Malpasset (1959) and Teton (1976) dam failures. However, lessons were learned from these experiences and, as expressed by Eggers (2016)1, today a mutual interdisciplinary respect exists for the importance of mature, field-experienced geological input for engineering purposes. Or, more simply, engineers now see the value of appropriately trained and experienced (engineering) geologists, and use them!

A potted history of engineering geology

Several detailed chronologies of the history of engineering geology history are available in the literature. For example, a detailed historical record of engineering geology beginning with William Smith was prepared by Galster (2004).2 Smith (1769-1839) is often considered to be the ‘Father of Engineering Geology’ (at least by the English) because not only did he contribute to the development of the modern geological map, but he was also involved in a range of engineering work in connection with mines, canals, irrigation and coastal defences through which he observed, documented and realised the significance of understanding the geology, and being able to predict it, for safe and efficient construction.

Arguably, the broad concepts of geology have been known and used in construction for thousands of years: engineering geology has (unknowingly) been an important scientific sub-discipline for as long as people have sought to construct their living environment. People soon learnt which caves were safe, where buildings could be built safely and where poor foundation conditions or the presence of geohazards meant that unacceptable risks were present. However, it was due to the great growth of geology as a major science in the early 19th century that the specific science and practice of engineering geology developed.

The first ever book entitled ‘Engineering Geology’ (which was published in England in 1880) was written by one William Henry Penning.3 The Introduction in Penning’s book begins with the sentence: “In the execution of engineering works, however scientific in design and clever in workmanship, failure has frequently usurped the place of success because due attention has not been paid to geological phenomena”.

During the twentieth century the attitude of engineers toward the importance and relevance of geological input into engineering works changed dramatically. Eggers (2016) suggests that the modern development of engineering geology occurred over the period from the 1920s to the 1960s, helped along by lessons learnt from a number of catastrophic engineering accidents (such as those listed above) that showed engineers around the world that the safety and economy of engineering projects required geologists with an appreciation of engineering principles, not just a classical education in geology. But Penning saw this way back In 1880 when he said “…it is not possible, nor even desirable, for all professional engineers to become proficient geologists… but they may, and with advantage, avail themselves of the labours of others..”

The development of ‘modern’ engineering geology was very much driven by large national building projects after the First and Second World Wars. Examples of major projects that promoted the development of engineering geology include the Hoover dam in the USA, constructed during the 1930s, the Snowy Mountains hydropower and irrigation scheme built between 1949 and 1972 in Australia, and the Waitaki, Waikato, Tongariro, Manapouri and Clutha hydropower schemes built between the 1930s and 1980s here in New Zealand. Standards and codes were developed, mostly during the 1960s–1980s, particularly for material descriptions and investigation methods.

Also during that period, particularly in the 1950s and 1960s, courses on geology were introduced into civil engineering undergraduate programmes in many countries and in some universities engineering subjects were incorporated into geology degrees. From this engineering geology emerged as a new discipline, culminating in the development of specialist courses in Engineering Geology in the 1960’s and 1970’s. Many of New Zealand’s senior or recently retired engineering geologists were trained in such courses in the UK, Australia or New Zealand. Others were trained in South Africa, the USA or Europe.

Development of engineering geology in New Zealand

The rapid economic expansions of the post-World War II years were the catalyst for engineering geology to become a cohesive profession (Williams 2016).4 The development of engineering geology in New Zealand prior to about 1970 was driven by major construction projects, particularly the hydro power stations, and was based largely on very good observations by geologists with no relevant training but experience in the geology of the site areas.

Waikato River Dams

The development of the Waikato Valley Hydro Electric Power Programme, which was carried out between 1929 and 1970, resulted in the construction of 8 dams and 9 power stations between Karapiro and Lake Taupo. The geology of the dam sites was determined by regional geologists from NZ Geological Survey and limited construction observation reports were prepared based on rare site visits. Most of these reports were prepared by Jim Healy (1940’s and 1950’s) or Bruce Thompson (from the mid 1950’s). The only original investigations/construction geological records for Arapuni were authored/co-authored by J Henderson (later Director of NZ Geological Survey) between 1920 and 1930. None of these people had any engineering background – both Jim Healy and Bruce Thompson were primarily volcanologists.

Waitaki River Dams

Following investigations in the late 1920’s, involving Pat Marshall (who wrote a report on the later-developed Aviemore site), Waitaki dam was constructed between 1932 and 1938, with extensions to the powerhouse in the early 1950’s. The only known geological information from that site was a mention in a regional mapping paper by Marwick (1935) and reference made to a report by Henderson in 1930. Marwick was a paleontologist; Henderson was primarily a mining geologist.

The Lake Tekapo Control Structure (1940) and the Tekapo A power station (commissioned 1947) were built either side of WW2 and the original Pukaki dam (since flooded) was commissioned in 1951. Ian McKellar and Horace Fyfe did a lot of the 1950s investigations for the Upper and Mid Waitaki projects. Benmore was constructed 1958 – 1963 and Aviemore in the period 1964 – 1968. None of these sites had a resident geologist during investigations or construction. Although occasional visits were made during construction by geologists from Christchurch, in particular Les Oborn and Graham Mansergh (for Benmore and Aviemore), there was little systematic recording of the ground conditions. Les was a graduate of the Otago School of Mines, Graham was a geologist with a special interest in Quaternary geology.

Clutha River Dams

Roxburgh dam was constructed between 1949 and 1956, and Hawea was constructed from 1956 to 1958. Bryce Wood and Ian McKellar (regional geologists from the Dunedin office of the NZ Geological Survey) made periodic site visits and reported their observations to the Ministry of Works but again there was no full time geologist on site capturing a complete record of the ground conditions at either site.

Manapouri Power Scheme

The original Manapouri scheme (completed between 1963 and 1971) brought a change of attitude to the value of on-site geologists, probably largely driven by the experience of the overseas contractor (Bechtel Pacific Corporation) and the complexity of the scheme. Kiwi engineering geologists associated with the Manapouri scheme were Royden Thomson who worked on the underground excavations (late 1960’s) and Graeme Halliday who worked on the Te Anau and Manapouri lake control structures from 1973 to 1976. Royden (a graduate of the Otago School of Mines) was employed by the contractor, Graeme was a Ministry of Works employee with a geology degree (who started on site as a chainman). Both of them were subsequently involved with the Clutha Valley Development project.5

Tongariro Power Scheme

TPD represented the first major commitment to engineering geology by the Ministry of Works and really represents the true ‘birth’ of engineering geology in New Zealand. This scheme, constructed between 1964 and 1983 involved a complex of dams, canals, tunnels and power stations, both surface and underground. By this time NZ Geological Survey had established (in 1965) its Engineering Geology Section led by Les Oborn.6

The first engineering geologists to provide full-time on site support in a secondment to TPD were Warwick Prebble and John Dow in the late 1960’s. They were later joined (or replaced) by Bernard Hegan, Graham Hancox, Brian Paterson, Terry Grammer, Chris Gulliver and (in 1977) Dick Beetham. None of them had specifically trained as engineering geologists; John Dow and Chris Gulliver had engineering degrees that included geology, while the young fella (Dick Beetham) had degrees in both engineering and geology.

Upper Waitaki Power Development

Les Oborn and Graham Mansergh provided geological support from Christchurch for the initial investigations for the Upper Waitaki Power Development during the 1960’s. The first full time engineering geologist on UWPD was Stuart Read from March 1972 through until September 1976. He was joined by an itinerant Scotsman, Jim McLean, who was there from 1975 until January 1977 when Don Macfarlane joined the team straight out of the University of NSW. Don remained on site until late 1981. All three of these site geologists had engineering geology degrees.

Clutha Valley Development

Royden Thomson joined the Geological Survey and was seconded to CVD in 1974, joined by Graeme Halliday (still with Ministry of Works) in 1976 and then Graham Salt (an engineer rather than a geologist) in 1978. Don Macfarlane transferred to CVD in late 1981 and the team was strengthened by the addition of Dick Beetham in the 1983. Jim McLean returned for a time also, working on Clyde dam, and was subsequently replaced by Mark Foley when he moved to Christchurch.

Maniototo Combined Power and Irrigation Scheme

Engineering geological support for this late 1970’s to early 1980’s scheme involving canals and a tunnel was provided by Brian Paterson and Jeff Bryant with some input from Royden Thomson. Kelvin Moody completed his Masters thesis on batter stability in schist along the canal.

Engineering Geology Section in Lower Hutt

As noted above, the NZ Geological Survey (now GNS Science) established an Engineering Geology Section under Les Oborn in about 1965. At the time there were few (if any) specialist engineering geologists in the country. It was Les who convinced the Ministry of Works and NZ Electricity Department of the value of engineering geology to major projects and (in my mind) can justifiably be called the “father of engineering geology in New Zealand”.

In the early 1970’s the team in Lower Hutt comprised Les Oborn, Nick Perrin and Bruce Riddolls, joined in mid 1970s by Graham Hancox on transfer from TPD and Ian Brown after a period providing full time support for the Auckland Rapid Transit investigations. Stuart Read relocated to Lower Hutt in 1978 after a stint travelling and working offshore but the team otherwise remained complete and unchanged until at least 1980. This group worked on a range of (mostly Government) engineering and research projects all around New Zealand, including providing additional support to those out on the big projects.

Training of engineering geologists

Few of the early engineering geologists in NZ had training in engineering geology, but they understood the relevance of geology to engineering and were able to communicate the important issues to the engineers better than a ‘classical’ geologist who commonly spoke a completely different language. This ability to communicate the importance of the geological factors was the key to the successful development of engineering geology as a separate profession in New Zealand (and worldwide).

According to Rogers (2002)7, the American Engineering Council for Professional Development pushed for the inclusion of engineering geology in undergraduate civil engineering courses from the 1950s so that by the mid 1970s nearly 80% of courses in the US included a compulsory engineering geology module. In the UK, Australia, New Zealand and many other countries, degree courses in Engineering Geology were first established in the late 1960’s and 1970’s, usually led by geologists with practical experience on large projects, most often dams and/or tunnels.

By the mid-1960s it had become obvious that there was a need for the local training of professionals who could provide quality geological input to engineering projects and work alongside engineers. At that time geologists at both Auckland and Canterbury universities had taught a paper ‘Geology for Engineers’ within the professional BE degree structure for several years but it was clear that more advanced and practical courses were needed.

In the mid 1960’s, Canterbury University appointed John Hill an Australian engineering geologist who had worked on dam construction projects in NSW (including Bendora dam, ACT) in the early 1960’s. He taught (some) geology to the civil engineering students and established an engineering geology course as part of the BSc (Hons) course: the first two graduates were Stuart Read and Ian Brown in 1971. The BSc (Hons) students did a range of classical geology papers and “Special Topics” (such as Rock Mechanics) that introduced them to engineering geology in their Honours year8.

David Bell (another Australian) joined the department in late 1972 and took over teaching the engineers about geology, then developed the hugely successful MSc programme in the late 1970’s.

Similarly, in the early 1970’s a Senior Lectureship in Engineering Geology was established by the University of Auckland and Warwick Prebble was appointed in 1975. He held a BSc in Geology from Victoria University and had worked for six years as combined regional geologist for the Geological Survey (DSIR) and project geologist for the Tongariro power project before moving to Auckland in 1971 to join Beca-Carter.

So, between the two universities, NZ was producing a small number but increasing of graduates with specialised engineering geology training during the 1970’s. Some of the Canterbury University engineering geology graduates of the 1970’s were Jeff Bryant, Guy Grocott and Grant Borrie, while over this period Auckland University graduates with some training in engineering geology included Simon Carryer, Wayne Russell, and Jarg Pettinga.

Also in the 1970’s Michael Selby was teaching geomorphology at Waikato University with a few students each year. Graduates in this period included Nick Rogers, Kevin Hind and David Burns. In the 1980’s Selby established an undergraduate engineering geology paper with a landform-based approach within the Earth Science degree, and a graduate paper more focussed on rock and soil mechanics principles in relation to slopes.

Outside of NZ Geological Survey

It has not been easy to identify people who worked as geologists and/or engineering geologists in other organisations before 1980 and it is probable that this account has missed some, several or most of them!

From 1924 until his retirement in 1940 Pat Marshall was employed as geologist and petrologist by the New Zealand Public Works Department in Wellington. His work was centred on geological problems associated with engineering projects9. This probably makes him the first full time engineering geologist in New Zealand.

W.N. Benson (Professor of Geology at Otago University 1917 to 1949) worked within the Dunedin area, and undertook studies that involved investigating new road- and rail-cuts and commercial and domestic excavations. His studies of mass movement, especially in urban areas and coastal areas north of the city, led to statements relating engineering hazards to particular local rock types.

In the late 1960’s and through the 1970’s the development of Engineering Geology in NZ was rather ad hoc and largely centered around the Geological Survey geologists seconded to the large infrastructure projects. But times were changing… in the universities and in the consultancies.

Tonkin & Taylor was established as a civil engineering testing business in 1959. Both Don Taylor and Ralph Tonkin were engineers. T+T’s first engineering geologist was Chris Gulliver (with both a BE and a BSc) in 1970, followed by Nick Rogers (with an Earth Science degree) who joined in the mid -70’s. Chris left T+T to join the team at TPD in 1975 but re-joined them in 1978. As noted above, Warwick Prebble moved to Beca from TPD in 1971 before joining the University.

Graham Cookson was a geologist with the Ministry of Works and Development in Dunedin from around 1969 to 1982, mainly supporting roading projects, while after completing his MSc in Jeff Bryant worked at the MWD Central Laboratory 1975-79 testing soils, soft rocks and real rocks. MWD employed Julie McMinn, who had a Diploma in Engineering Geology, in Dunedin in the

early 1980’s.

In Wellington Tony Mahoney was a geologist with Brickell Moss Rankine and Hill through the 1970s, with particular expertise on assessing the stability of slopes and foundations (that continued into the 1990s).

David Burns embarked on his career in engineering geology (in about 1980) as a soils technician with Worleys. He held a Masters in Earth Science (from Waikato) and was another example of a geologist who learned engineering geology on the job.

Bob McKelvey came to engineering geology via an NZCE (early 1970’s) and a Geology degree (late 1970’s) and it is likely that others followed a similar path.

Where to after 1980?

The creation of good training courses, ongoing development projects and increasing awareness of natural hazards and environmental issues led to a rapid growth in the numbers of engineering geologists in NZ from the mid-1980s onwards.

From 1980, the Canterbury MSc in Engineering Geology usually had 5 to 10 students per year – and the University also taught the BSc (Hons) course and offered a postgraduate Diploma in Engineering Geology. Graduates in the early to mid-1980’s included Gary Smith, Tim Browne and Mark Foley.

In the early 1980’s Bernard Hegan joined the exodus from the NZ Geological Survey to grow the engineering geology expertise of T+T, Ian Brown formed his own company, Bruce Riddolls joined Worleys to establish an engineering geology team, after which he formed his own company. Mark Yetton joined Soils & Foundations in Christchurch (in 1983) and other consultancies retained some of the newly trained engineering geologists emerging from the universities, while others went overseas for experience.

Doug Johnson and Debbie Fellows both worked at CVD as summer students in the early-mid 1980’s, and Kelvin Moody spent summers with Jeff Bryant who was then the site geologist on the new highway through the Cromwell Gorge.

The Clyde landslides stabilisation project (1989-1992) saw the largest single concentration of engineering geologists on any single NZ project up until that time, with the on site team peaking at 28 (including summer students Mark McKenzie, Richard Justice and Virginia Cunningham). Graduates on the site included David Barrell, Tim Coote, David Stewart, Paul Horrey and Linda Price.

By the late 1980’s our universities were training more engineering geologists than we needed so many of the graduates sought overseas experience. Over the intervening years engineering geologists within NZ have become spread across many organisations, including CRIs, regional councils and consultancies. Some of those who went overseas have returned but others have built successful careers elsewhere while overseas-trained engineering geologists are now fairly common in NZ. It is a massive change from the period before 1980!

Final Remarks

Remember where we came from!

Penning, way back in 1880, first coined the term ‘engineering geology’. He had the understanding to realise that “.. the geological conditions which affect engineering and similar works are, mainly, the extent of the various strata, their lithological character, and their order of succession. It matters not what may have been the forms of Life during the ages when the strata were deposited…”.

It took both the civil engineering and geology professions a long time to realise the truth of this statement, but it happened – and we can thank Penning for setting the career path we have chosen!

Footnote: Penning’s 1880 book can be downloaded (free) from https://ia800203.us.archive.org/15/items/engineeringgeolo00pennrich/engineeringgeolo00pennrich.pdf

Acknowledgements

Many people willingly provided information (in varying levels of detail) for this article. They included Ann Williams, Ian Walsh, Warwick Prebble, David Bell, Stuart Read, Bernard Hegan, Chris Gulliver, Vicki Moon, John Dow, Bob McKelvey, Graeme Halliday, Greg Saul, Gary Smith, Peter Foster, Graham Ramsay, and Geoff Farquhar. Stuart Read provided critical comment on the draft; Nick Perrin found the photograph of the 1977 Engineering Geology Section team.

All errors and omissions are the responsibility of the author!

References

1 Eggers, M.J. (2016). Diversity in the science and practice of engineering geology. Geological Society, London, Engineering Geology Special Publications, 27, 1-18, 21 September 2016. https://doi.org/10.1144/EGSP27.1

2 Galster, R. W. (2004). The Origins and Growth of Engineering Geology and its Professional Associations. Association of Engineering Geology Special Publication 19, CD-ROM, P. O. Box 460518, Denver, Colorado.

3 Penning originally trained as an engineer then joined the (British) Geological Survey in 1867

4 Williams, J. (2016). Engineering Geology – Definitions and Historical Development Applications in Life Support Systems. http://www.aegstl.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/APPLIED-GEOLOGY-5000-YRS-EOLSS-A.pdf

5 The Second Manapouri Tailrace Tunnel constructed between 1997 and 2001 to increase the efficiency and output of the power station involved a new generation of engineering geologists.

6 Leslie Eric Oborn (1920-2011) was Chief Engineering Geologist from 1965 until his retirement. Les studied at the Otago School of Mines 1947 to 1950 and then began work at NZ Geological Survey in Christchurch where he became involved in (among other things) investigations for the Benmore dam. This led to an ongoing interest in geology for engineering projects. In 1964, Les transferred to Lower Hutt where he established the Engineering Geology Section of NZ Geological Survey and convinced the Ministry of Works and NZ Electricity Department of the value of engineering geologists to major projects.

7 Rogers, J.D. (2002). Disappearing practice opportunities: why are owners and engineers taking increased risks? What can be done to counter this threat? In: Proceedings of a Symposium “Visioning the future of engineering geology: stewardship and sustainability,” 26 September 2002, Reno, Nevada at the Joint Annual Meeting of the Association of Engineering Geologists (AEG) and the American Institute of Professional Geologists (AIPG). Special Publication 14 (on CD-ROM). Association of Engineering Geologists, Denver, Colorado, 14p

8 The original students were required to gain entry into Engineering school to participate in the soil mechanics courses

9 https://teara.govt.nz/en/biographies/3m44/marshall-patrick