Local slope stability in Auckland’s North Shore East Coast Bays Formation rocks

Thoughts on Auckland North Shore East Coast Bays Formation rock slope stability and engineering design from field investigation and laboratory test results

Abstract

As New Zealand’s largest city, Auckland faces various natural hazards, including landslides. The East Coast Bays Formation (ECBF) slopes along Auckland’s North Shore coasts present challenges for residential houses due to their lithological character and variability. To better understand the stability of such ECBF slopes and provide insights for future geotechnical design, this paper presents findings from field observations of Auckland North Shore ECBF slope failures, engineering structures, and laboratory tests on collected samples. Two sites were investigated and sampled ECBF rocks include sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, with varying levels of cementation. Laboratory density, porosity, bulk, shear and Young’s moduli, were measured under different saturation conditions. These experimental results were then linked to the geological features of the ECBF slopes, with a slope stability analysis model that provides insights into improved geotechnical design on ECBF slope. The study found that groundwater and rock erosion susceptibility should be the primary considerations for maintaining ECBF slope stability in the long term. Appropriate building setback distances should ideally be developed using site-specific properties of the local geology, rather than regional extrapolations based on generalised parameters or engineering designs.

1. Introduction

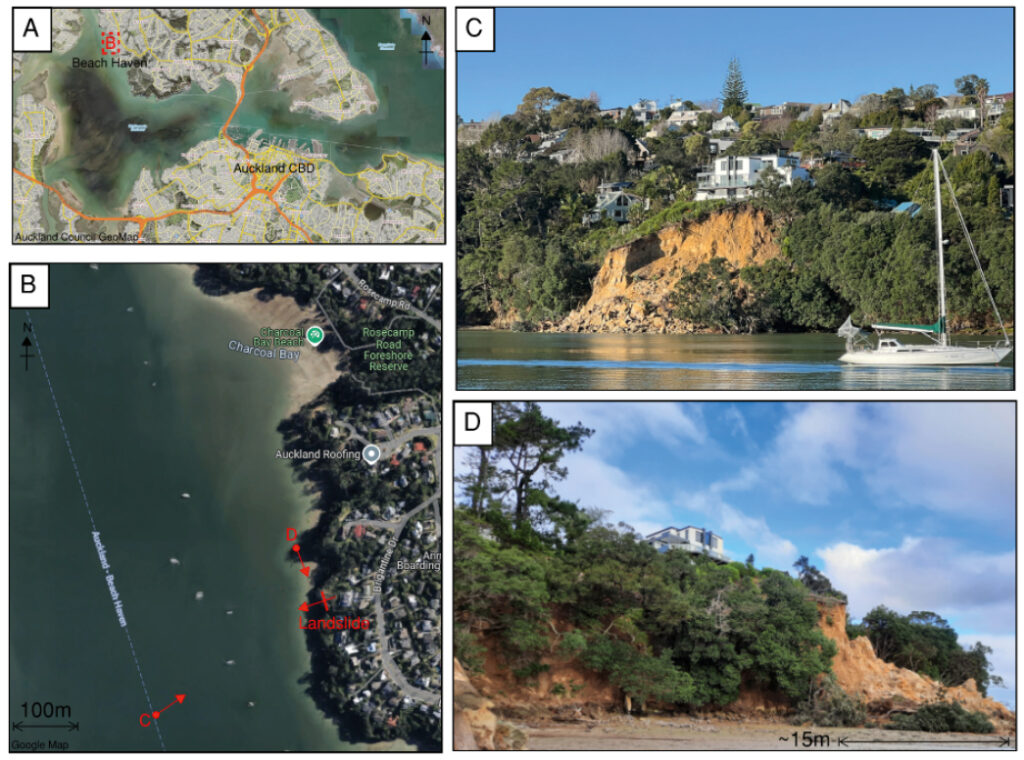

Landslides in the Auckland area are a significant natural hazard that challenges both existing and future city development (Brook & Nicoll, 2024). The Auckland region is particularly susceptible to rainfall-triggered landslides, and indeed Hancox and Nelis (2009) stated that much of Auckland is at high or moderate risk from landslides. In recent years, rainstorms have triggered thousands of landslides across the Auckland region, including in 2017 Cyclone Debbie and the Tasman Tempest (Palma et al., 2020), and in 2023, the Auckland Anniversary Storm and Cyclone Gabrielle (Roberts, 2023; Brook & Nicoll, 2024). Such storms can cause multiple occurrence regional landslide events (MORLEs; Crozier, 2005), where thousands of landslides occur over a matter of hours and cause serious impacts and challenges for territorial authority responses (Massey et al., 2024). Auckland’s North Shore area can feature high relief terrain, with large numbers of residential houses developed near to the East Coast Bay Formation (ECBF) cliff edges, with some setback distances of only a few meters (Jongens et al., 2007; Fleetwood et al., 2020). During extreme rainfall events, the rise in the groundwater table increases pore water pressure, reduces effective normal stress, and consequently, reduces slope shear strength. This process will occur at different rates in different ECBF lithofacies, which consist of sandstone, siltstone, or mudstone rock, with varying levels of cementation, porosity, permeability and strength (Black & Riddolls, 2006; Fleetwood et al., 2020). Even after extreme rainfall, minor changes in ground load, additional light rain, or wave action may still cause further slips and cliff recession (de Lange & Moon, 2005; Moon et al., 2003; Moon, & Terry, 1994; Williams et al., 2004; Palma et al., 2020; Buckeridge, 1995). An example of such slope instability is a landslide that occurred in July 2022 in Beach Haven on the northern side of Waitematā Harbour (Figure 1). This slope failure shows how large volumes of sedimentary rock and overlying residual soils and colluvium fail as a planar landslide type (Hungr et al., 2014). This Beach Haven slip example was from a residential backyard to the nearshore zone after heavy rains in the previous month before the landslide. Indeed, from March to August 2022, saw Auckland experience more than 149% of the historical average rainfall records (NIWA, 2023), causing instability of many slopes on the North Shore, affecting residences. This storm event and associated slope failures provided an opportunity to conduct studies on the North Shore ECBF rock slopes, to gain geotechnical design insights and improve ECBF slope stability sustainably in the North Shore area. This included field investigation, laboratory tests and slope stability modelling, as outlined below.

As outlined in studies by Paterson and Prebble (2004), de Lange and Moon (2005) and Brook and Nicoll (2024), landslides in ECBF rock can be triggered by a combination of factors, such as wave action, rainfall, specific geological features, as well as land use change on the slope itself. Thus, this case study focused on Auckland North Shore slopes at Beach Haven and Narrow Neck, with the following objectives:

- Identify the geological features of slope, existing landslides and engineering structures in the field, and classify the ECBF rocks from the selected areas.

- Perform laboratory tests on samples collected from the field sites, measuring, and calculating the parameters such as elastic moduli, density, and porosity at dry and water-saturation conditions.

- Combine the results obtained from field and laboratory tests, linking them to a slope stability model to obtain insights into geotechnical design.

2. Field investigation

2.1 Geological features of Auckland’s North Shore slopes

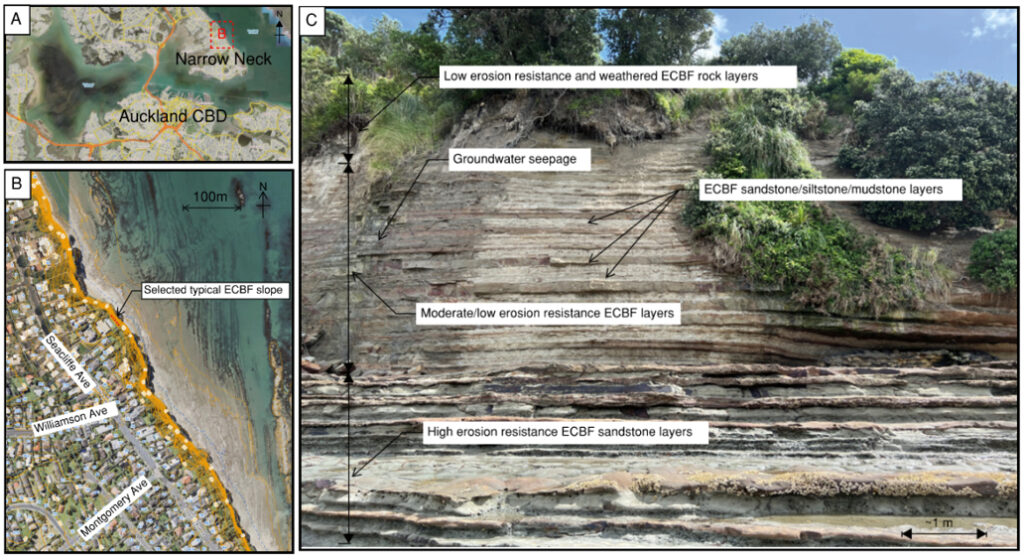

Like the Beach Haven ECBF slope (Figure 1), Narrow Neck is another North Shore slope area with typical ECBF slopes, which is more accessible for obtaining rock samples. Narrow Neck is characterised by a steeper slope angle and less vegetation on the slope surface compared to Beach Haven. A representative Narrow Neck slope is shown in Figure 2 and has a maximum angle of 70-80°, ranging in height from 25-35 m above sea level. Vegetation and trees are found at elevations of 20 to 25 m above sea level, which corresponds to the backyard areas of residential housing on the slope tops, on more weathered materials. The entire ECBF slope may present a varied weathered profile, as indicated by Adhikary (2001), which creates potential engineering design challenges.

The steep slope section begins at around 2-3 m above sea level and consists of weakly-cemented easily erodible ECBF rocks. The gentler slope angle at the bottom of the slope features significantly more cemented sandstone, which offers higher erosion resistance against wave energy and groundwater. These weaker layers consist of horizontally bedded sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, which is a characteristic sequence reported for the Waitematā Basin (e.g. Shane et al., 2010). Overall, sandstone layers tend to be more erosion-resistant than the adjacent siltstone and mudstone layers. The latter in particular, commonly exhibit a higher sensitivity to swelling and shrinking effects due to the smectite content (Black & Riddolls, 2006). This compromises rock integrity during wetting and drying cycles, due to uneven deformation and the internal stresses that develop (e.g. Gokceoglu et al., 2000). With groundwater or tidal and wave inundation, these layers may exhibit slaking, developing a mesh pattern of cracks, reducing the rock mass strength (Selby, 1980), further reducing erosion resistance. In contrast, the sandstone layers are less affected by cycles of wetting and drying, due to their cementation, which enhances intact strength and resistance to crushing effects. An exception to this pattern can occur when the cementing minerals are dominated by smectite clays, as has been shown to exist in some ECBF units (Black & Riddolls, 2006). From the site characterisation across the Narrow Neck area slopes, it is evident that ECBF rock types can be broadly classified into sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, each with varying levels of cementation and erosion resistance.

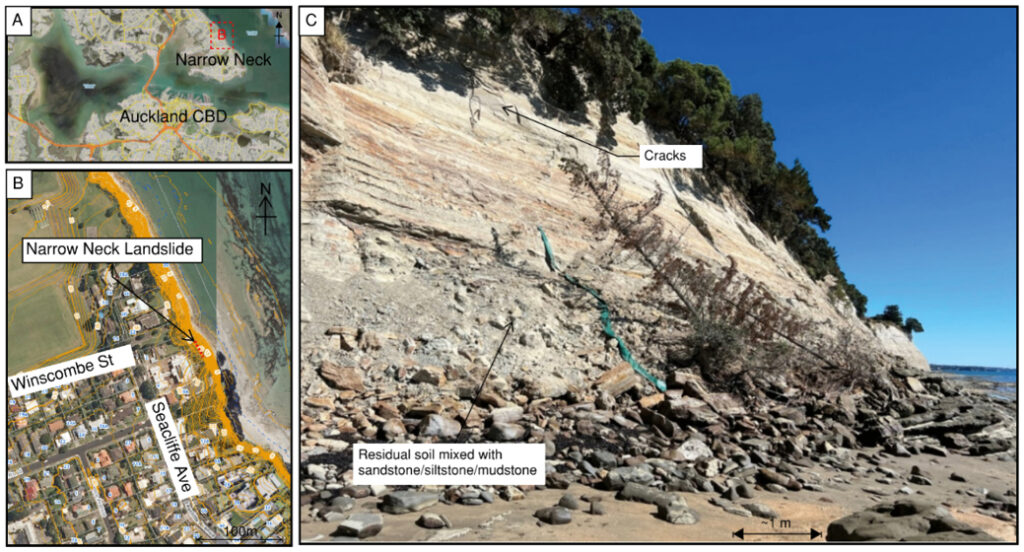

2.2 Examples of ECBF slope failures

During the site walk along the Narrow Neck coastline formed on ECBF slopes, a recent landslide was observed ~20-minute walk north of Narrow Neck Beach. Figure 3 shows the presence of debris composed of sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone units at the slope toe, also including vegetation, and drainage structures that had been displaced from the top of the slope. Debris included rock blocks up to 2 m, as well as ground down boulder-and cobble-sized clasts, and residual soils. During the field visits, open defects (e.g. fractures) indicated potential for further detachment of blocks and slope failure (Figure 3). Indeed, observed defects and small overhangs extending <0.5m out of slope near its crest indicated the potential for triggering of further slope failures during future rainfall events. These observations are similar to the slopes visited at Beach Haven in Figure 1.

It is worth noting that the Narrow Neck area slopes generally have clean slope toes with minimal landslide debris visible along the coastline. However, the entire coastline is vulnerable to landsliding, and debris from historical landslides likely provides a temporary armouring of the slope toe, before it is eventually removed by marine erosion. Gradually, the slope foot is exposed again to direct marine erosion. This model of ECBF coastal slope evolution was also indicated locally by Auckland Council (2020) and Paterson and Prebble (2004). Internationally, this model of coastal slope evolution corresponds to Category B (i.e. medium height cliffs undergoing cyclic failure in the form of periodic large slumps) of Barton (2015). These types of coastal landslides were described by Hutchinson (1973) as those where the rate of marine erosion exceeds the rate of supply of colluvial material by slope erosion/weathering. This re-exposure of the cliffs once slope toe debris has been eroded, means that slope failure can be initiated again by factors including rainfall, groundwater changes, marine erosion, or possibly, additional ground surcharge from land development above. Hence, the slope may appear stable in the short-term, but cycles of erosion and groundwater changes cause ongoing failure and cliff recession in the long-term (Buckeridge, 1995). This cyclic period is unknown for ECBF cliffs, but examples for Category B (e.g. Barton, 2015) London Clay cliffs on the North Kent Coast indicate an erosion cyclic period of ~30-40 years, and slightly longer in the stronger units.

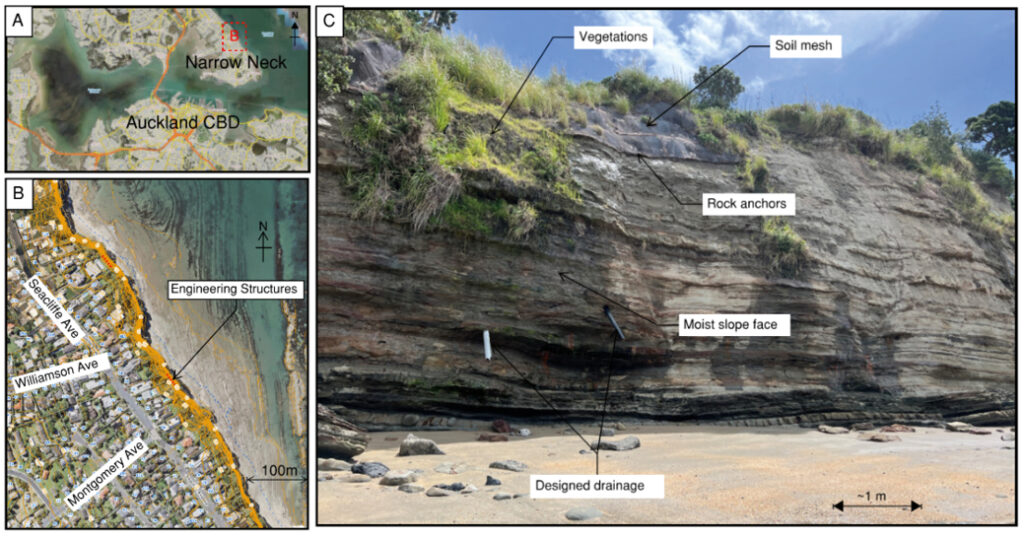

2.3 Existing structures for improving slope stability

During the site walk along the Narrow Neck coastline, it was observed that a variety of slope engineering methods had been installed, and that some of these had improved local slope stability (Figure 4). Drainage pipes were installed in the lower part of the cliff, to facilitate groundwater drainage. It appears vegetation was intentionally maintained, but with minimal trees and vegetation at the slope edge. While vegetation and tree roots can enhance the stability of the soils at the slope top, the residual soils can become saturated and fail as earthflows down the cliff, sometimes entraining weathered rock. At Narrow Neck, additional slope engineering structures include soil mesh, used in conjunction with vegetation, and rock anchors to reinforce weathered ECBF rocks immediately below the residual soils (Figure 4). Rock anchors, secured with mesh, were identified and appear to be part of a specific engineering design implemented to enhance local slope stability.

While the slope engineering methods identified in Figure 4 may provide local support, it is questionable as to whether such engineering is simply piecemeal, with little prospect of limiting the rate of slope failure and cliff recession over the coming decades. An additional effect is that if adjacent cliffs remain unprotected, the stabilised cliff section may then protrude seaward, losing lateral support on each side, and increasing vulnerability to marine erosion (e.g. Moore & Davis, 2015).

3. Laboratory tests

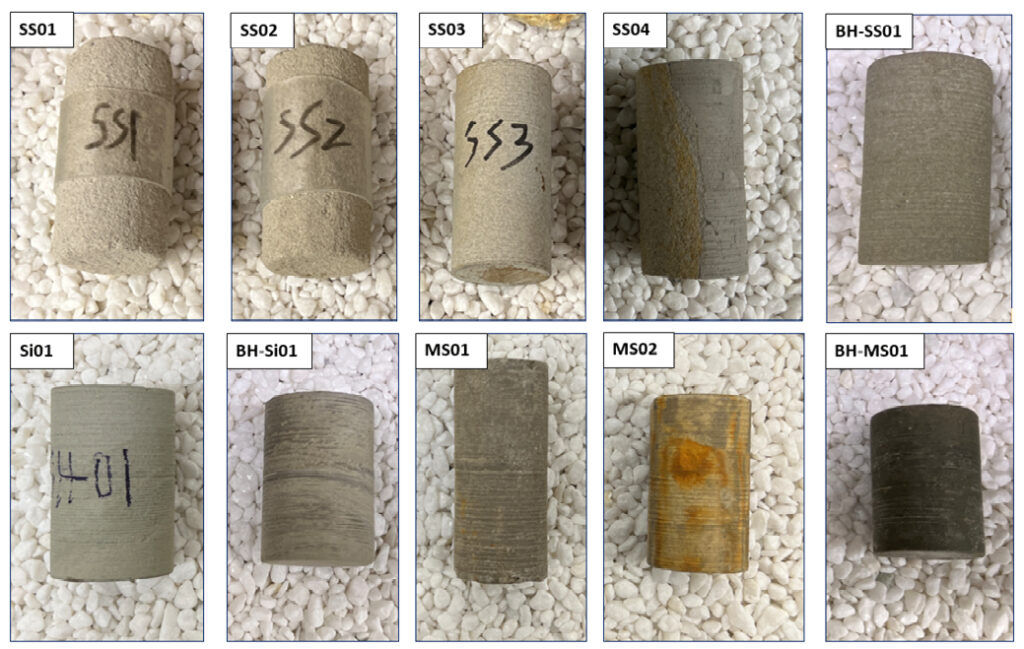

The field investigation provided a useful conceptual understanding of typical failures in ECBF coastal slopes. To gain further insights into cliff failure mechanisms, laboratory testing was used to determine how rock properties vary across different ECBF lithofacies, and how rock strength changes with different groundwater conditions. This study uses ultrasonic wave velocity tests for P- and S-waves to estimate the dynamic elastic moduli, as well as pycnometer tests, on the different ECBF lithofacies (Figure 5). Rock samples range from sandstone (with varying levels of cementation) to siltstone and mudstone. For comparison, more compacted/consolidated ECBF rock samples were selected from a borehole at 6-11 m below Quay Street, to understand the overburdened rock properties within the slope. Since geophysical (wave speed) tests are non-destructive, laboratory results provide information on the density, porosity, dynamic bulk, shear and Young’s moduli of the same sample under both saturated and dry conditions for the sandstone sample group (e.g. Cai et al., 2000). It was observed during the site investigation that mudstones and siltstones are vulnerable to changes in water content. Therefore, these lithofacies were tested in their natural (as-it-is) and saturated conditions for comparisons. Tests under fully dry conditions were not undertaken, as the drying process caused cracking in the rock samples.

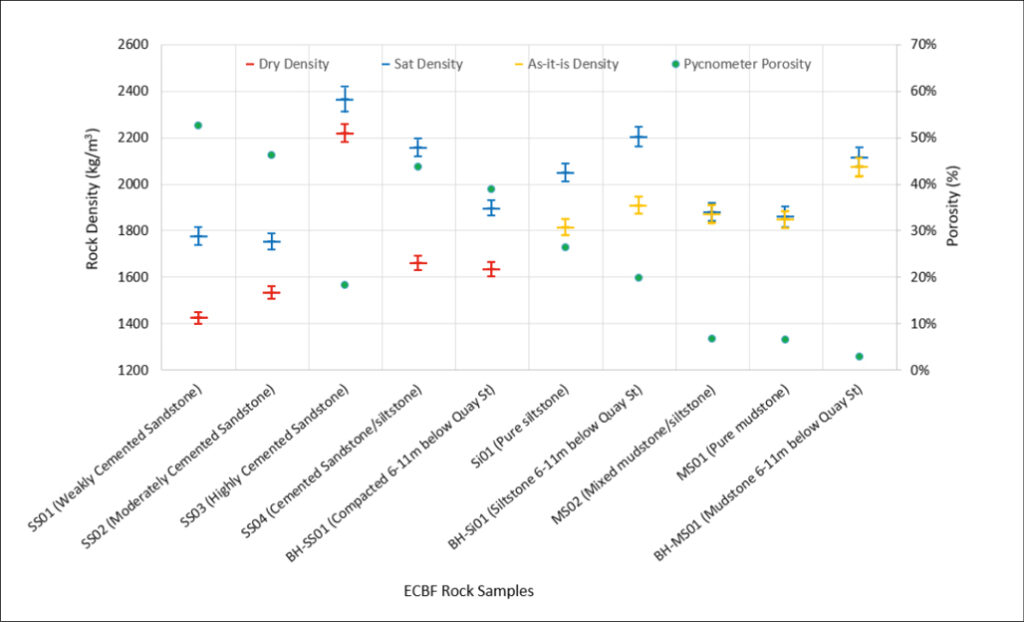

3.1 ECBF rock samples vs. compaction, density and porosity

Porosity and density of the different lithofacies tested is shown in Figure 6. This illustrates the effects of varying degrees of cementation/compaction in ECBF sandstone, siltstone, and mudstone, tested under different saturation conditions. Most of the sandstone sample group (SS01 to BH-SS01) wave speeds were measured in both saturated and dry density, while porosity was measured with the pycnometer for the sandstone in dry condition (Figure 6). Overall, sandstone with higher cementation (representing the lower portion of the slopes at the study sites) exhibit lower porosity due to increased clay and other mineral fills, leading to higher density. Rocks with higher porosity (i.e. sandstones) overall show a larger difference between the dry and saturated density, implying that this lithofacies might be more sensitive to groundwater changes. The cemented siltstone/sandstone (SS04) presents porosity and density behaviours that encompass properties of both lithofacies, typically resulting in slightly lower porosity and higher density (Figure 6). Cementation is greatly influenced by the proportion between sand-sized, silt-sized or clay-sized particles, as well as the mineralogy of the cement (Black & Riddolls, 2006; Fleetwood et al., 2020).

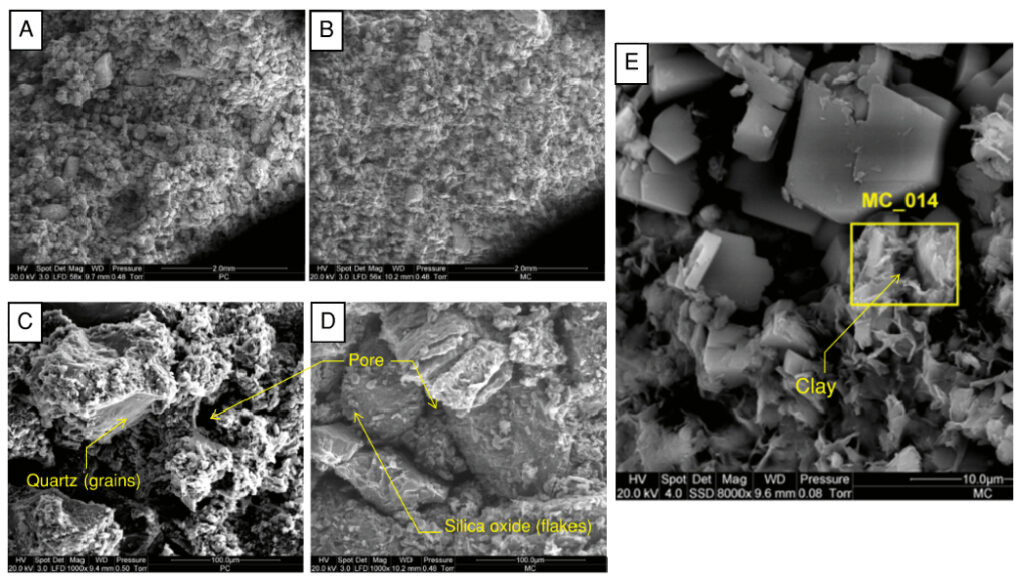

Figure 7 shows Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) images of ECBF sandstone samples SS01 and SS02, highlighting quartz grains and clay cementation between them as a typical example of ECBF rock structures.

Density and porosity of the more cohesive siltstone and mudstone samples (Si01 to BH-MS01) were made on saturated and natural (as-it-is) rocks, to prevent unexpected cracking. Based on the principles of gas pycnometer measurement (Razavifar et al., 2021) and given that the as-it-is samples are already partially saturated, the pycnometer porosity offers insight into the void ratio available for additional water saturation. From Figure 6, it is evident that the mudstones in the field had already achieved near full saturation, even a few days after the last rainfall when the rock samples were collected. This indicates that mudstone is more likely to retain water content within its structure due to its low permeability. This characteristic is not as pronounced in the coarser-grained siltstone, as its permeability is not as low as that of mudstone, so siltstones may dry out more quickly after rainfall. In comparison, sandstones with the greater porosity will also exhibit the greatest permeability. Regarding the ECBF slope features at Narrow Neck, although the siltstone and mudstone layers are vulnerable to cycles of wetting and drying as a result of groundwater fluctuations, it takes a long time for these layers to dry up due to their low permeability. Drying out only affects the very surface (<10 mm depth) veneer of the rock, causing a “mesh” pattern of cracks, which is why the mudstone or siltstone layer’s existing rock cracks remain temporarily stable. Since water content is well-preserved, there are minimal porosity/density changes to the mudstones within the slope. But, once any layers exhibiting drying cracks, parts of the cliff mudstones are removed by marine erosion or groundwater flow. The underlying layer is newly exposed and the wetting -drying cycle continues, weakening the rock. This is explaining, in-part, the prevailing long-term stability issues evident for mudstone ECBF rock layers (Li, 2023).

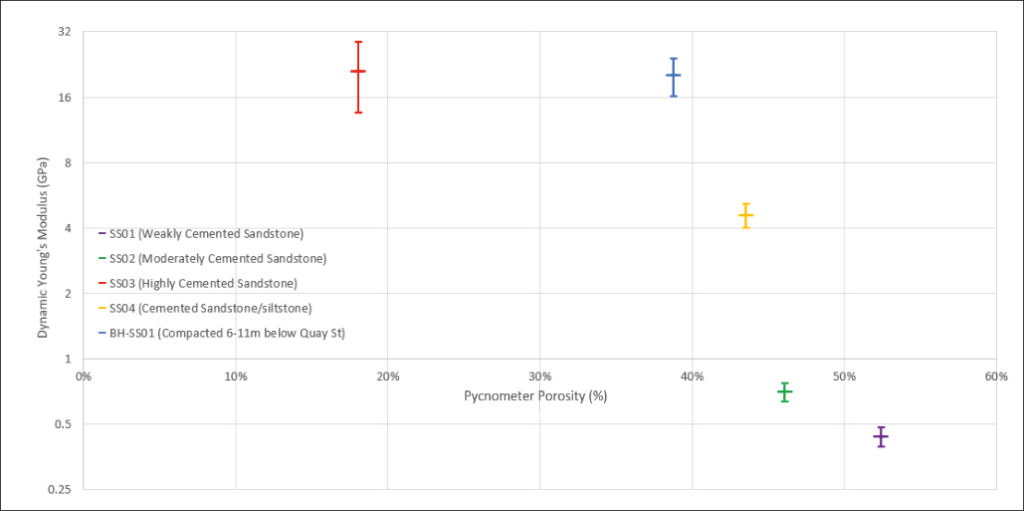

3.2 Porosity vs. Young’s modulus for ECBF sandstone in dry condition

Figure 8 illustrates the association between Young’s modulus and porosity for the ECBF sandstone lithofacies, taking into account varying degrees of cementation, compaction, and the presence of silt-sized particles, in dry conditions. The results indicate that the more cemented and compacted ECBF rocks exhibit higher dynamic Young’s modulus and lower porosity. This indicates the importance of ECBF rock stiffness and strength, which are largely influenced by grain compaction and the cementation between them, as highlighted in the SEMs in Figure 7. For sandstone that is not strongly cemented, as well as for mudstone and siltstone groups in saturated conditions, the saturation process weakens the original rock sample. The laboratory tests encountered issues with measurements of some of the saturated samples as the rocks disintegrated during testing. For weakly cemented sandstone, their vulnerability is also evident in field investigations, where changes in groundwater conditions can crack or alter the rock’s intact properties.

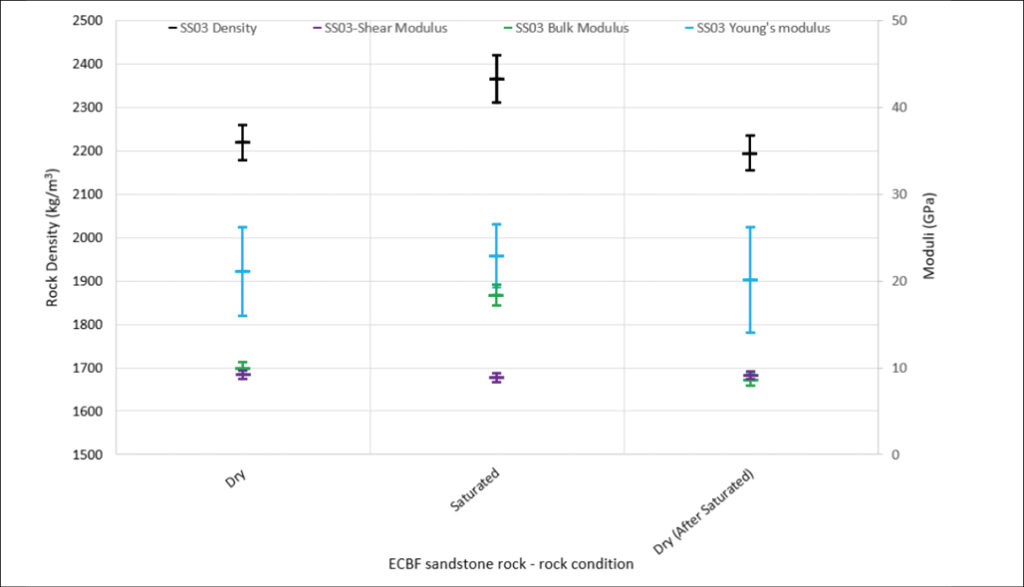

3.3 Effects of ECBF rock saturation process

To further explore how saturation influences the properties of the ECBF sandstones, this study tested a well-cemented sandstone before and after the saturation process. Only the well-cemented sandstone was tested for the effects of water-saturation. Negligible changes in shear modulus from dry to saturated conditions are observed (Figure 9). This is an expected outcome as the rock shear strength is insensitive to saturating fluids (i.e. the shear modulus of a fluid is zero; Cai et al., 2020). However, bulk and Young’s moduli values are expected to increase as water saturation increases. This is because the higher compressibility of water compared to the stiffness of entire rock (Papageorgiou & Chapman, 2015).

The density and elastic moduli of the same rock dry before and after the saturation process slightly decreases (Figure 9). This suggests that the laboratory saturation process had indeed altered the rock microstructure. This accords with the study of Cai et al. (2020), who reported that the saturation may initiate microstructural damage, and change the rock intact properties and strength. While the saturation process might have slightly altered the rock original microstructure and texture, it is important to note that field conditions involve repeated cycles of wetting (rainwater and sea water) and drying. This suggests that the saturation and drying cycle can also weaken the rocks making them more prone to erosion (e.g. Gokceoglu et al., 2000). This implies that the ECBF rock layers are sensitive to fluctuations in groundwater levels, which can lead to progressive stiffness weakening in the long term (Li, 2023).

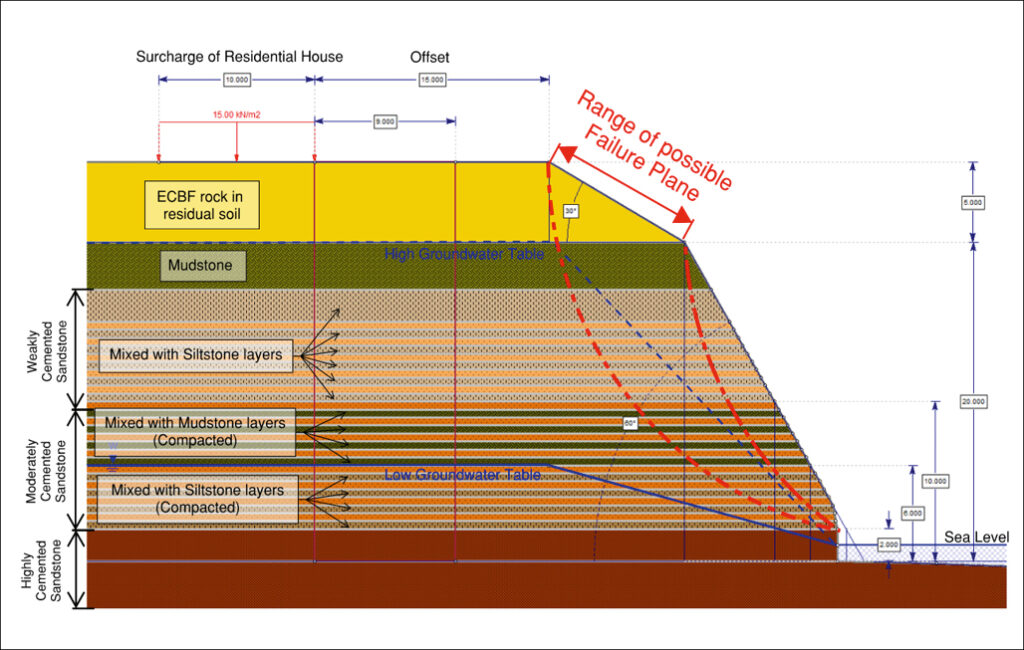

4. Slope stability analysis

To further interpret the stability of the ECBF slopes, the limit equilibrium software tool, Slide2, has been utilised here to model the geological features found at Narrow Neck. Additional information, including groundwater data provided by Westerhoff et al. (2018) and GNS (2023), and the slope cross-section for 2 Seacliffe Avenue residential property (NZGD, 2023), was also used in the model. Utilising measured laboratory data (Li, 2023), the effect of changes in the groundwater table on the slope Factor of Safety was examined. Without slope toe support or landslide debris at the toe, the critical failure plane extends locally along the slope face (Figure 10). This provides an indication of stability under the given slope geometry, groundwater conditions, and rock properties, which also corresponds with the slope failure features found during site visits. However, limitations exist in such modelling, due to several factors. These include (1) the time-dependent weakening of cohesive siltstone and mudstone due to mesh cracking, (2) slope face recession (which alters slope geometry), and (3) changes in rock properties caused by wetting and drying cycles from rainwater and seawater. Importantly, these are the key factors that contribute to the instability of ECBF slopes in the long term. Therefore, for engineering design of such ECBF cliff slopes, rather than analysing existing Factor of Safety, it is more worthwhile to simply focus on regulating groundwater conditions and controlling toe erosion.

5. Geotechnical design insights

Based on field investigations and laboratory test results from the Narrow Neck area, it appears that the instability of North Shore ECBF slopes is a long-term issue influenced by various factors (Acharya-Chowdhury et al., 2024). These long-term factors include, but are not limited to, groundwater fluctuations and coastal erosion. Indeed, slope failure and concomitant cliff recession is not just a short-term problem caused by rapidly rising groundwater levels, altered pore pressure, and decreased effective stress from rainfall triggering slope failures (c.f. Barton, 2015). Nevertheless, the local impact of these long and short-term processes can be significantly affected by the type of ECBF lithofacies present, the degree of rock grain cementation, and compaction/consolidation due to overburden pressures. Moreover, the cycle of groundwater fluctuations and erosion may permanently weaken the rock structure, as illustrated in Figure 9. Marine erosion (Sunamura, 1992) can also erode weakened layers of cracked mudstone or siltstone, and remove any landslide debris armouring the cliff toe, leading to ongoing cliff failure, posing a hazard to residential developments on the crest.

Slope stability problems at North Shore sea cliffs are not non-trivial, and have site specific effects, including local geology. Ideally, slope stability improvements should take local geology into account, and this may extend along several residential property boundaries. Where faults are present within the ECBF cliffs, this can create additional engineering geological issues (Fleetwood et al., 2020), especially where fault planes intersect and dip out of slope. However, the engineering design for ECBF slopes should also focus more on long-term solutions. This may include (1) drainage to regulate groundwater conditions and minimise changes in rock properties from wetting and drying cycles, (2) seawalls and/or retaining walls to reduce the effect of toe erosion, and (3) preservation/nourishment of toe debris from landslides.

6. Conclusions

Based on the field investigation and laboratory test results, it has been determined that groundwater control should be the major consideration at these sites. Varied ECBF lithofacies, levels of cementation, and compaction due to overburden pressure can result in different responses to water content changes and erosion. More cemented and compacted/consolidated sandstone is more durable against groundwater changes and erosion, while siltstone and mudstone, which are more susceptible to erosion and frequent changes in water content, can even be permanently weakened. From the findings for the ECBF rocks extracted from the field and tested in the lab, geotechnical design should account for ECBF slope stability with appropriate building setback distances for the long term. In addition, controlling rapid groundwater changes from extreme rainfall and maintaining consistent groundwater conditions within the slope, alongside retaining the slope using structures, should mitigate development of slope instability development.

Acknowledgement

The conclusions presented in this paper are part of the studies conducted for K. Li Master of Engineering Geology degree at the University of Auckland. We would like to express my deepest appreciation to laboratory technician, Jeff Melster. K. Li also extends his gratitude to the Aurecon Auckland tunnel and geology teams for their encouragement and support during his part-time studies at the university.

References

Acharya-Chowdhury, L., Dickson, M.E., Norton, K.P., Rowland, J.V., Hall, B., & Stephenson, W.J. (2024). Reconciling short- and long-term measurements of coastal cliff erosion rates. Engineering Geology, 341, 107703.

Adhikary, T. (2001). Weathering profiles and characteristics of Waitemata rocks in the Auckland region. New Zealand Geomechanics News, 62, 70-77.

Black, P., & Riddolls, B. (2006). East Coast Bays Formation sandstone: When and why does it behave like claystone? New Zealand Geomechanics News, 72, 29-30.

Brook, M.S., & Nicoll, C. (2024). Brief report of fatal rainfall-triggered landslides from record-breaking 2023 storms in Auckland, New Zealand. Landslides, 21, 1581-1589.

Buckeridge, J. (1995). Land stability in urban sites of the North Shore, Auckland, NZ. In International Symposium on Landslides, pp. 2129-2136.

Cai, X., Zhou, Z., Zang, H., & Song, Z. (2020), Water saturation effects on dynamic behavior and microstructure damage of sandstone: phenomena and mechanisms, Engineering Geology, 276, 105760.

Crozier, M. (2005). Multiple-occurrence regional landslide events in New Zealand: Hazard management issues. Landslides, 2, 247-256.

de Lange, W. P., & Moon, V. G. (2005). Estimating long-term cliff recession rates from shore platform widths. Engineering Geology, 80(3-4), 292-301.

Fleetwood, B., Brook, M.S., Brink, G., Richards, N.R., Adam, L., & Black, P.M. (2020). Characterization of a highly heterogeneous flysch deposit and excavation implications: case study from Auckland, New Zealand. Bulletin of Engineering Geology and the Environment, 79, 4565-4578.

GNS. (2023), GNS National Water Table interactive map. Retrieved from GNS Science: https://www.gns.cri.nz/data-and-resources/gns-national-water-table-interactive-map/

Gokceoglu, C., Ulusay, R., & Sonmez, H. (2000). Factors affecting the durability of selected weak and clay-bearing rocks from Turkey, with particular emphasis on the influence of the number of drying and wetting cycles. Engineering Geology, 57(3-4), 215-237.

Hancox, G.T., & Nelis, S. (2009). Landslides caused by the June–August 2008 rainfall in Auckland and Wellington, New Zealand. GNS Science Report 2009/04. 30pp

Hungr, O., Leroueil, S., & Picarelli, L. (2014). The Varnes classification of landslide types, an update. Landslides, 11, 167-194.

Hutchinson, J.N. (1973). The response of London Clay cliffs to differing rates of toe erosion. Estratto da geologia applicata e idrogeologia, vol 8, Part 1. Bari, Italy.

Jongens, R., Gibb, J., & Alloway, B.V. (2007). A new hazard zonation methodology applied to residentially developed sea-cliffs with very low erosion rates, East Coast Bays, Auckland, New Zealand. Natural Hazards, 40, 233-244.

Li, K. (2023). Auckland East Coast Bay Formation Rocks in Relation to Local Slope Stability. Master of Engineering Geology thesis, University of Auckland.

Massey, C., Leith, K., White, R., Bidmead, J., McColl, S., Jones, K., & Selvaraj, S. (2024). Initial insights from mapping 150,000 landslides triggered by Cyclone Gabrielle. New Zealand Geomechanics News, 107, 32-40.

Moon, V,G. & Healy, T. (1994). Mechanisms of Coastal Cliff Retreat and Hazard Zone Delineation in Soft Flysch Deposits. Journal of Coastal Research, 10 (3), 663-680.

Moon, V., Lange de, W., & Lange de, W. (2003), Mudslides developed on Waitematā group rocks, Tawharanui peninsula, North Auckland, New Zealand Geographer, 59 (2), 44-53.

Moore, R., & Davis, G. (2015). Cliff instability and erosion management in England and Wales. Journal of Coastal Conservation, 19, 771-784.

NIWA (2023). Aotearoa New Zealand climate summary: 2022. Retrieved from NIWA National Climate Centra. https://niwa.co.nz/sites/default/files/2022_Annual_Climate_Summary_FINAL_v3.pdf

NZGD. (2023), New Zealand Geotechnical Database. Retrieved from New Zealand Geotechnical Database: https://www.nzgd.org.nz/.

Palma, A., Garrill, R., Brook, M.S., Richards, N., & Tunnicliffe, J. (2020), Reactivation of coastal landsliding at Sunkist Bay, Auckland, following ex-tropical cyclone Debbie, 5 April 2017, Landslides, 17, 2659-2669.

Papageorgiou, G., & Chapman, M. (2015). Multifluid squirt flow and hysteresis effects on the bulk modulus–water saturation relationship. Geophysical Journal International, 203(2), 814-817.

Paterson, R., & W. Prebble (2004), Engineering geology and coastal cliff erosion at Takapuna, Auckland, New Zealand, in 9th Australia New Zealand Conference on Geomechanics. NZ Geotechnical Society and Australian Geomechanics Society, Auckland, 775–781.

Razavifar, M., Mukhametdinova, A., Nikooee, E. et al. (2021). Rock porous structure characterization: a critical assessment of various state-of-the-art techniques. Transport in Porous Media, 136, 431-456.

Selby, M.J. (1980). A rock mass strength classification for geomorphic purposes: with tests from Antarctica and New Zealand. Zeitschrift fur Geomorphologie, 24, 31-51.

Shane, P., Strachan, L. J., & Smith, I. (2010). Redefining the Waitemata Basin, New Zealand: A new tectonic, magmatic, and basin evolution model at a subduction terminus in the SW Pacific. Geochemistry, Geophysics, Geosystems, 11(4).

Sunamura, T. (1992). Geomorphology of Rocky Coasts. Wiley, New York.

Auckland Council. (2020), Predicting Auckland’s Exposure to Coastal Instability and Erosion. Retrieved from Auckland Council. https://www.knowledgeauckland.org.nz/media/2432/tr2020-021-predicting-aucklands-exposure-to-coastal-instability-and-erosion.pdf.

Westerhoff, R., White, P., & Miguez-Macho, G. (2018), Application of an improved global-scale groundwater model for water table estimation across New Zealand. Hydrology and Earth System Sciences, 22(12), 6449-6472.

Williams, A., & Prebble, W. (2004), Engineering properties of clay seams within the Waitemata Group rocks of Auckland. Proceedings 9th Australia New Zealand conference on geomechanics, Auckland, 2, 840-844.